– by Zarnain Abedi

Throughout the years, women have had great involvement in making art, either as creators and innovators of new forms of artistic expressions, patrons, collectors, as an inspiration, or as art historians and critics. They have constantly been integral to the institution of art.. Despite engaging with the art world in so many ways, most women artists have been either suppressed or neglected in the narrative of art history. They have faced challenges due to gender biases, it was difficult for them to receive training, sell their work or even simply create art.

According to a Roman writer, Pliny the Elder, from the 1st century C.E., the first drawing ever was made by a woman named Dibutades. She traced the silhouette of her lover on a wall. There have always been glimpses and examples of women’s art within male-driven societies. Even when it comes to the earliest works of art known, like the voluptuous ‘Venus of Willendorf’ from 25000 B.C.E. On the other hand, objects like weavings and clothing have always been associated with women’s craft, from the story of Penelope’s courageous weaving in Homer’s epic tale the Odyssey, from 800 B.C.E., to the 11th century Bayeaux tapestry, a 270-foot long fabric document telling the story of medieval Britain, likely woven and embroidered by women.

Even though the Western mythology tells us that a woman was the first artist, women artists have gotten very little attention until the end of the 20th century. Women were barely featured in the stories of great artists. Even when they were, they were described as “unusually talented women who overcame the limitations of their gender in order to excel in what was believed to be a masculine field”. Mary Beale was a successful British portraitist in the late 1600s. But most of her success was attributed to her husband since he oversaw their studio and showcased her works as experiments in the methods that he had developed. Gwen John made a self-portrait which appears isolated and scrutinised. She felt like women were constantly struggling for recognition in a field dominated by men, including her brother Augustus.

Through the centuries, women have been systematically excluded from the records of art history. This was due to multiple factors: art forms like textile and the “decorative arts” were often dismissed as craft and not “fine art”; many women weren’t permitted to pursue a general education, let alone training in arts. As artist and instructor Hans Hoffmann once “complimented” the significant abstract expressionist artist Lee, “This is so good you wouldn’t know it was done by a woman.”

In the 1960s, with equal rights and upcoming feminist movements, in USA and Europe, there was a boom of women studying and teaching in art schools. These art schools became centres of feminist activity, which encouraged the representation of women in the art galleries. This movement redefined the potential of women in art and paved the way for many women artists practicing today.

Linda Nochlin’s article “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” was published in Art News in the year 1971. In this essay she explained assumptions from the title’s question. She considered the nature of art along with why the notions of artistic genius have only been reserved for men like Michelangelo. Nochlin debated that the obstructions of the society have prevented women from pursuing art, including restrictions on educating women in art academies.

In the 20th century, things began to change for women artists as well as for women across the domestic and public spheres. A new women’s movement, with an emphasis on the advocacy of equal rights, organisations devoted to women’s interests, and a new generation of female professionals and artists transformed the traditionally male-driving social structure around the world. These social shifts, which began to emerge at the beginning of the century, developed further with the advent of World War I and expanding global unrest, propelling more women into the workforce and exposing them to social, professional, and political situations that had previously been limited to men.

With an improved sense of confidence in the art scene, many women artists chose to address personal and universal issues of identity. The works of refugee artists such as Mona Hatoum and Shirin Neshat express stories of their loss and vision through conflicting countries, gender roles and cultures. Artist Sonia Boyce’s film, photographs, and paintings brought racism to light.

Other female artists use their art to express the specific issues they face as women. In the 1970s, Margaret Harrison used irony to portray the objectification women face. In the same decade, artist Linder drew on the anti-establishment politics of Dada to create photomontages that overthrew traditional media pictures into unnerving statements. Filmmaker Barbara Hammer used shots of her own body to advocate for more open representation of lesbian sexuality. Today, artists like Cornelia Parker are highlight how the “idealised” images of the female body are unrealistic when compared to the figures of real women.

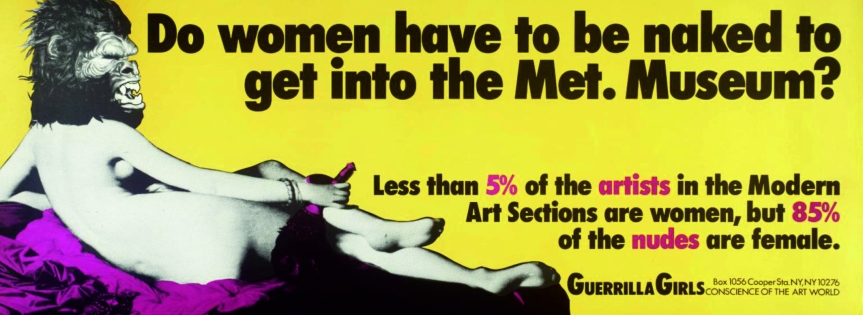

By calling attention to identity, sexuality, politics, and history, women artists have dominated the art debates for the last several decades. Groups like the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous group of women artists and art professionals, work to fight discrimination and raise awareness of the issues that women face in the art world. The group formed in New York City in 1985 with the mission of bringing gender and racial inequality into focus within the greater arts community. The group employs culture jamming in the form of posters, books, billboards, and public appearances to expose discrimination and corruption. They do this wearing gorilla masks to take the focus away from their identities.

Looking out for women artists who had been excluded from main stream art has encouraged a redefinition of art practices, making us rethink what we call the “decorative arts,” installation art, and performance art “revolving around the artists” bodies. By urging scholars to seek out the “forgotten” women, the project continues on today. There is no single “female art” but rather that art shapes and is shaped by culture, that it conveys cultural ideas about beauty, gender, and power, and that it can be a powerful tool to question issues of race, class, and identity.